The great unknown

It has been said that data can draw inferences between diaper purchases and beer sales. That it can displace oil and identify love. But can it, really? While there is a lot of talk about data – or more accurately, big data – there is a scarcity of knowledge. Before diving into the world of industrial data usage, we’d like to approach the subject from a popular science perspective.

Big data bang

The surge in digitalization is evident in the global volume of data – the so-called datasphere. In 2010 the aggregate volume of data generated, captured and replicated amounted to 2 zettabytes (that’s a figure with 21 zeros). By 2025 the datasphere is expected to grow to a whopping 181 zettabytes, a 90-fold increase since 2010. If you were to store this amount of data on DVDs, the stack of disks (without their cases) would be roughly 9.4 million kilometers high, or more than 24 times the distance between the Earth and the moon.

It all began with the bubonic plague

The principle of viewing data as a source of knowledge is not new. Throughout the centuries, people have attempted time and again to systematically utilize information for decision-making. As far back as 300 BC or so, the ancient Egyptians tried to record all of the data in the works in the Library of Alexandria. The Romans carefully studied statistics related to their military as a means of determining the optimal distribution of armed forces. The first evidence of working with ‘big data’, as we understand it today, occurred in 1663. While examining death rates in England during the bubonic plague that was then ravaging Europe, John Graunt worked with what was a vast amount of information for the time. That made him one of the first people to employ statistical data analysis.

Better than oil

Oil, mobile telephony, energy, finance: this is how the world’s five largest companies made their money in 2008. Today, four of the five biggest are technology companies, some of which make their money purely with data or cloud services. This illustrates how data beats oil now. You can duplicate it. It’s reusable. And it’s an almost infinite resource.

The dark side of AI

In 2017 Amazon was forced to scrap an algorithm that unintentionally favored male job applicants over female candidates. Another algorithm used within the US justice system calculated inordinately high recidivism rates among Black defendants and offenders, which meant that they tended to receive longer prison sentences than their White counterparts and had less chance of being freed on bail. These are only two examples that suggest data and artificial intelligence are not necessarily objective, because they adopt the biases of their programmers. As Forbes business magazine reported, in the tech industry these workers are 80 percent male and the majority are White. That makes more diversity and less bias in data analysis an important task for the future.

The legend of beer and diapers

While not entirely true, the following is a helpful story that has made the rounds in seminars and literature for decades. According to the legend, in the 90s retail giant Walmart analyzed its sales receipts and discovered a rise in demand for beer and diapers on Friday evenings. Young fathers apparently were taking advantage of the family weekend shopping trip to stock up on a couple of six packs. Creative employees then placed the beer in the vicinity of the infant supplies. Sales went through the roof. Although those involved said there was no correlation between the sales figures and the gender or age of the buyers, the effect is undisputed – and provides a powerful explanation of the principle behind data mining.

Fish with fingers

To err is human. That means even artificial intelligence, fed with data from humans, can go wrong. Researchers at the University of Tübingen in Germany trained a neural network to identify images of tench, a species of fish. But when they wanted to know which characteristics the AI technology relied on to identify the fish, and had it show them the most important pixels used for this purpose, they were in for a surprise: a selection of rosy human fingers against a green background. It turned out that most of the images in the dataset showed anglers holding a tench in their hands. That gave the AI technology the wrong idea: it concluded that the fingers were part of the fish.

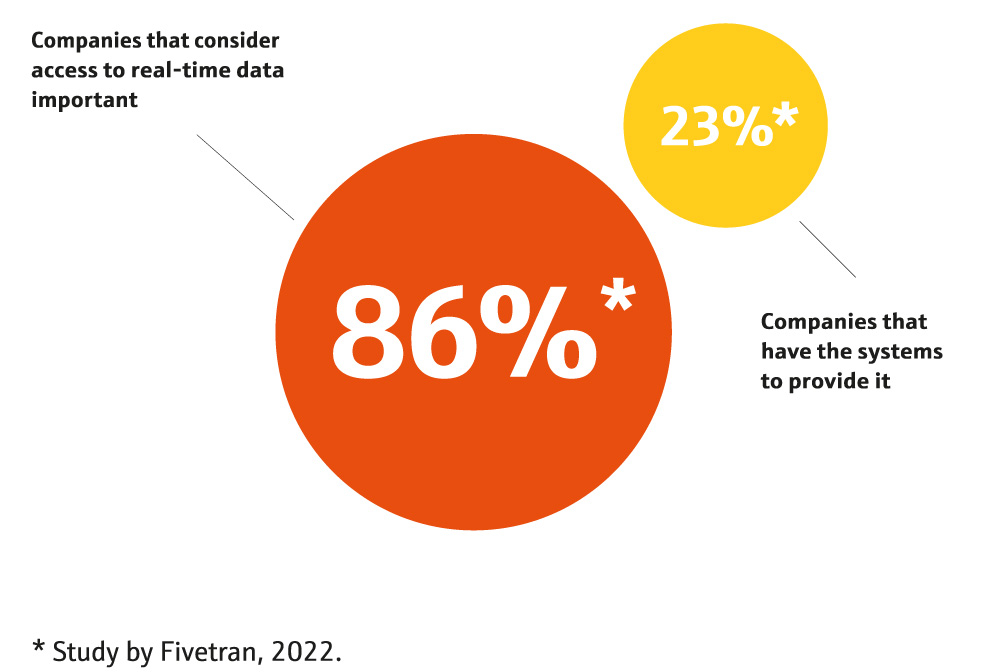

Is it already in real time?

Everyone wants it, but only a few can create it.

Data match = love?

Online dating services have been booming for years. But they won’t reveal exactly how their algorithms work. The assumption is that the more similar two people are in terms of their values and preferences, the better the chances for a long and happy relationship. Researchers at Northwestern University in Illinois claim this is just a lot of hot air. In the US journal Psychological Science, they explain that personality tests cannot tell how two people will get on or whether their sense of humor is the same. Nor do the tests ask about stressful periods in life or financial problems, which can place strain on a relationship. So for long-term love, it’s better to search around in real life.

“ It is clear that we are all drowning in a sea of information. The challenge is to learn to swim in that sea, rather than drown in it.”

Peter Lyman (1940–2007),

author and computer scientist at the University of California, Berkeley

Published 28.10.2022, last updated 21.11.2022.

Dive into the world of the process industry through new exciting stories every month with our «changes» newsletter!