Hand in hand

Crises, wars, pandemics: The challenges facing supply chains are enormous. We need to be bold in preparing for them, says Robert Friedmann, chairman of the Central Management Board of the Würth Group. With Matthias Altendorf, Endress+Hauser’s Supervisory Board president, he discusses the advantages of family businesses and why it ultimately all comes down to people.

Mr Friedmann, when was the last time you experienced a significant supply chain problem at the Würth Group?

Friedmann: We often experience shortages of various materials, especially plastics and metals. For us, the key question is what’s causing them. The problem as we see it is that many companies are cutting capacity too quickly and too early. This was particularly so during the coronavirus pandemic, when many of our suppliers slammed on the brakes and slashed their inventories. The problem came afterwards, when it took three years to recover from such severe cutbacks. So, bottlenecks persisted well beyond the crisis that caused them.

How did you respond to the Covid crisis and the resulting market collapse?

Friedmann: At the time, we took advice from an economist who basically told us, “This lockdown won’t last forever. Hang in there!” Holding out like that wasn’t practicable in every case, but our general ambition was to stick it out for the longest time possible. Which paid off in the end. We made it through the crisis in good shape because we maintained product availability for customers. Although it needs saying that as a family-owned business, we have the financial strength necessary for such staying power.

Mr Altendorf, how does a company like Endress+Hauser brace itself for supply chain problems?

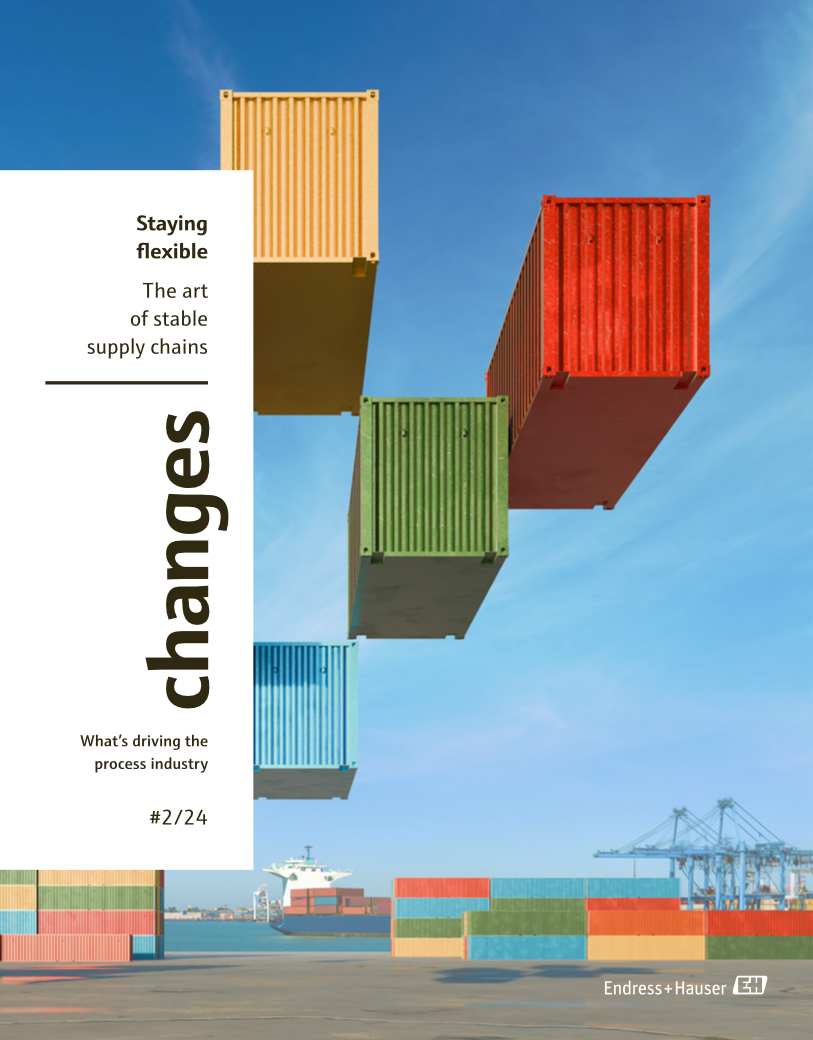

Altendorf: Some events are near-impossible to prepare for. Think of a pandemic closing Chinese ports, or a container ship getting stuck in the Suez Canal. But still, there are measures you can take to minimize risks and thus add resiliency to your supply chain. For instance, with upstream products we don’t just rely on one supplier but have several spread across different economic areas. Then there’s warehousing: here we don’t seek to optimize from a purely financial perspective, but rather from our customers’ point of view. And I agree here with Mr Friedmann that family-owned businesses do have certain advantages over publicly listed corporations.

Friedmann: As I see it, crises aren’t likely to occur any less frequently in the coming years. We have to get used to the disruptions caused by political acts, wars, natural disasters and pandemics.

What does ‘get used to’ mean, exactly?

Friedmann: It means positioning ourselves to effectively handle potential disruptions. Which is far from easy to do, as supply chain management makes plain. The people who work on our supply chain have particularly challenging jobs.

"As I see it, crises aren’t likely to occur any less frequently in the coming years.”

Robert Friedmann

Chairman of the Central Management Board of the Würth Group

How does Würth being a family-owned business affect relationships with your suppliers and customers?

Friedmann: This very encounter is a great example of that. Endress+Hauser is a long-standing customer of ours, placing thousands of orders every year. When Mr Altendorf and I get into discussion, it’s not about key figures and prices, but rather values and what fosters our companies’ unique cultures. It’s not about the way things appear to be, but the way things really are.

Altendorf: I have an example to illustrate the relationship question. On a recent trip to India, I got into conversation with our suppliers. They had suffered a lot under Covid. And yet they kept on delivering. That benefited us and our customers. A number of these suppliers struggled with liquidity at times. They were close to going under, but we helped them out in ways like paying in advance for deliveries, trusting that we would receive the goods in due course. What I’m trying to say is that our supply chain is made up of partners. We know each other, we trust each other, we recognize that we can depend on each other, and we act accordingly.

How do growing sustainability demands affect supply chain management?

Friedmann: That’s a question to examine from two perspectives. First, there is no denying that it falls to everyone to be more sustainable in the way we work, live and conduct business. The measures we take here need discussing in terms of their speed, appropriateness and efficiency. The second perspective considers the high regulatory requirements placed on companies in the EU. One of those is the Supply Chain Due Diligence Act. Operating under these rules requires a huge amount of effort that companies from Switzerland, China or the USA don’t have to match. I take a critical view of the imbalance this creates.

Could things work just as well without rules?

Friedmann: I don’t think we can achieve comprehensive change across entire economies just on the basis of well-meaning appeals. Getting there takes regulations – but these should apply to everyone.

Altendorf: The key thing for the transformation is to strike a balance between sustainability on the one hand and economic success and social compatibility on the other. Dogmatism and rushing things won’t help. It’s important to keep a sense of balance and moderation. Restructuring an economy within the space of a decade simply isn’t possible. It’s a task that will span generations.

“Our supply chain is made up of partners. We know each other, we trust each other, we recognize that we can depend on each other, and we act accordingly.”

Matthias Altendorf

President of the Supervisory Board of the Endress+Hauser Group

One driver of the transformation is digitalization, where Endress+Hauser is heavily invested. So how are digital solutions changing supply chains?

Altendorf: As a good example, take our Global Logistics Operations Center in Ireland. There we can digitally track every package leaving an Endress+Hauser facility. And that’s not all: We can steer packages around, correcting their route when necessary. This is an effective tool, especially in times of volatile goods transport chains.

At the Reinhold Würth Innovation Center CURIO, you are working on customized AI solutions to increase logistics flexibility. How far have you gotten with this?

Friedmann: All sorts of wonderful applications exist in theory. We’re looking for applications that can help us right now. We’ve already had some successes: We can now use AI systems for more accurate prediction of customer behavior or to optimize the route a salesperson takes to visit their customers. Our planning team is also benefiting from the possibilities of AI. Logistics used to be a department that just dealt with existing systems. Today, the logistics people are also exploring the potential of machine learning. A lot has happened here.

Altendorf: Job profiles in all areas of logistics have changed significantly and will continue to do so. I firmly believe that digitalization will not cost any jobs in the long run, but it will change almost every profession.

Around 44,000 people in the Würth Group worldwide work in sales. How important is the human factor in sales?

Friedmann: We still see our salespeople as crucially important; they are the ones who establish and maintain contact between the customers and us. For us it’s only natural that sales has a big say on issues such as product availability and quality.

Altendorf: Selling is an emotional process, so friendliness naturally counts among Endress+Hauser’s defining values, along with sustainability, commitment and excellence. Contact with customers via our sales force matters because that is our only means to discovering their motivations, where they use our products, how their business is developing and what they are trying to achieve. This makes our salespeople trusted confidants and advisors. For customers, they are the reassurance that what we sell actually works.

Friedmann: Our segment deals with a lot of craftspeople, who tend to like the human touch. Although these days it’s essential to make use of digitalization, automation and AI, ultimately, the business we do is always between people.

Published 02.12.2024, last updated 09.12.2024.

Dive into the world of the process industry through new exciting stories every month with our «changes» newsletter!