The butterfly effect

American meteorologist Edward Lorenz brought chaos theory into the public consciousness with his notion that a butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil can set off a tornado in Texas. That same concept applies equally to supply chains, where even seemingly insignificant glitches can have major repercussions.

Modern supply chains are optimized for efficiency. That means any disruption, however small, can quickly trigger an unpredictable chain of events. One such disruption occurred in the summer of 2022, when the war in Ukraine made natural gas so hard to come by and expensive in Europe that many fertilizer producers were forced to reduce or even shut down production at their ammonia plants using natural gas as a feedstock. Scheduled maintenance shutdowns of ammonia plants in the USA only exacerbated the situation. This butterfly wing flap in agribusiness precipitated a chain of events that ultimately took the fizz out of the beverage industry – literally and figuratively. Until the crisis, most industrial food-grade CO2 used for bottling and carbonating soft drinks had been a by-product of ammonia manufacture. The resulting shortages drove numerous breweries, soft drink producers and mineral water bottlers to scale back their production.

FROM INTEGRATED PRODUCTION TO GLOBAL SUPPLY CHAINS

In the chemical industry, this type of interconnectedness – where the by-products of one process are used for other processes – is known as integrated production. Chemical giants like Dow and BASF have turned this kind of integrated supply chain into an art form that significantly enhances their production sites’ resource efficiency, and hence economic viability. But there is a downside: a broken link in the chain can have unforeseen consequences for other processes, both at the plant in question and far beyond – as we have seen in the beverage industry example. What’s more, a supplier who cannot guarantee supply risks losing revenue and market share, with the added sting that many customers may never return.

And yet, reliability of supply is just one among a growing number of challenges that companies must navigate in managing their supply chains. Indeed, while supply chain globalization has in recent years created new market opportunities and possibilities for cooperation, it has also driven an increase in complexity and vulnerability.

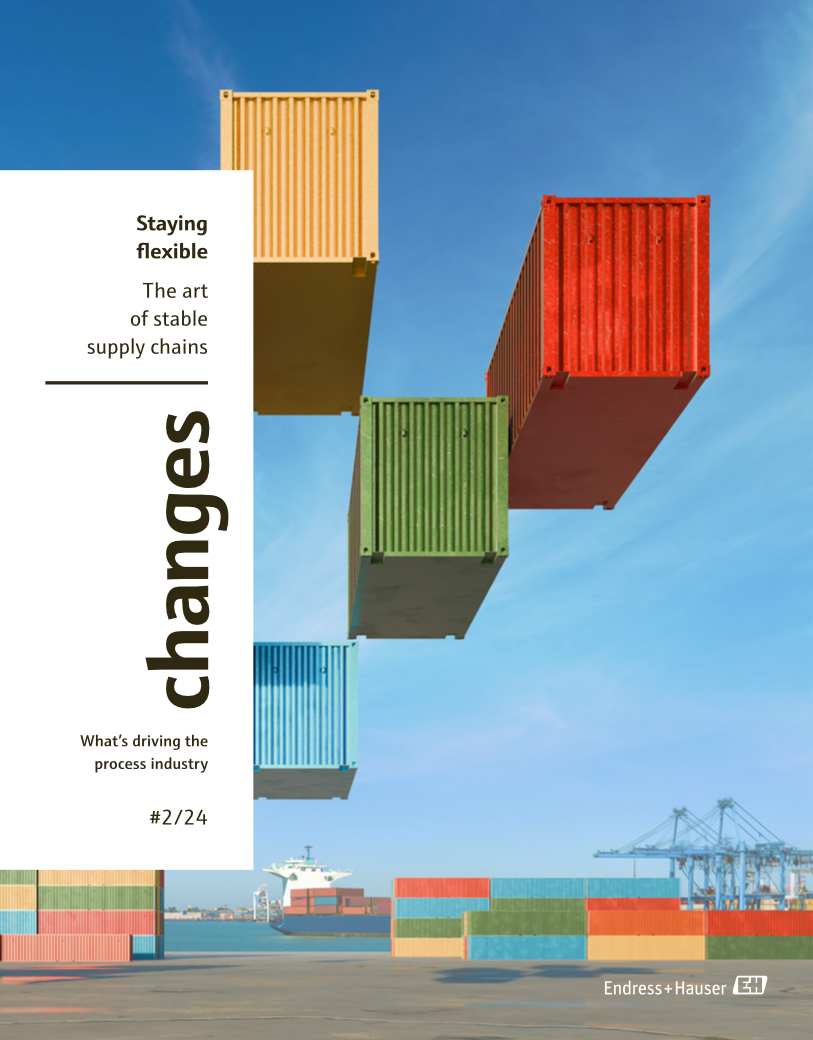

Supply chains across all industries – whether chemical, life sciences, automotive or machinery manufacturing – have been under pressure in recent times. Uncertainty and risks continue to grow. This upending of many things taken for granted by the big industrial players of the world came to a head during the pandemic years. As if the 2020 and 2021 closures of China’s ports to halt the spread of the virus weren’t enough, the Ever Given container ship ran aground in the Suez Canal, and most recently another one – the Dali – collided with a bridge in Baltimore. Suddenly, supply routes once considered reliable were anything but.

Meanwhile, the ongoing drought in Central America is causing a bottleneck in the Panama Canal shipping lane because there is not enough water available for the locks along the 80-kilometer waterway. Growing geopolitical tensions are also contributing to the uncertainty. Repeated attacks on merchant vessels in the Red Sea by Houthi rebels in Yemen, for example, have frequently made shipping companies divert cargoes to the significantly longer route around Africa. Shipping group Maersk estimates that this rerouting results in a 15 to 20 percent global reduction in freight capacity between Asia and Europe.

COMPLEXITY NEEDS STABILITY

This mounting uncertainty is particularly problematic for the manufacture of highly complex products that rely on numerous raw materials, intermediate products and specialized components. A stable, predictable and plannable supply chain is essential here, so the focus has shifted to risk management. Some pessimists are already predicting the end of globalization as the debate turns to localization, nearshoring and friendshoring, and logistics and supply chain managers increasingly concern themselves with supply chain resilience. The fundamental question here is how to make supply chains less vulnerable to disruptions. An increasing number of companies are recognizing that the answer lies in transforming existing supply chains. By doing so, they will be better placed not only to navigate complex supply chain challenges, but also to address the ever more exacting demands of customers and regulators.

Yet another challenge for the process manufacturing industry, with its energy-intensive operations, is to achieve sustainable production and a defossilized – if not decarbonized – value chain. Most companies in the industry are committed to the Paris Agreement target of achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. In fact, many companies have set even more ambitious targets.

The greatest challenge for these companies is not the greenhouse gases emitted within their own operations, but the indirect emissions that arise in their value chains – known as Scope 3 emissions. The European Chemical Industry Council (Cefic) estimates that Scope 3 emissions account for more than 70 percent of CO2 emissions in the chemical industry. And lawmakers companies in Europe are subject to the reporting requirements of the new EU directive on corporate sustainability reporting (CSRD), which obliges them to publish regular sustainability reports. Even the US Securities and Exchange Commission now requires companies to disclose climate-related risks and data. Similar regulations are also being advanced in the Asia-Pacific region.

“The contribution of the supply chain for sustainability will be crucial.”

Dr Hanno Brümmer,

executive vice president of supply chain and logistics, Covestro

15%

to 20% of freight capacity between Europe and the Far East has been lost, according to Maersk, because merchant vessels are having to detour around the Red Sea due to ongoing attacks by Houthi rebels.

ACHIEVING FULL VISIBILITY

There is an axiom in process automation that applies equally well to supply chains: If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it. How much CO2 is emitted in the production of raw materials and their packaging before they even arrive at the plant? How big is the carbon footprint of supplied electronics or housing components? Most producers have no ready answers to such questions. And that means taking a new approach to communications between suppliers and their customers.

End-to-end visibility has thus become something of a buzzword among supply chain managers. They want to thoroughly understand their entire supply chain network. That involves conducting strict audits of their suppliers’ operational practices and safety protocols. What’s more, the audits are not confined to aspects like ability to deliver, sustainability measures and compliance with regulations such as the EU’s recently adopted Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). Also under scrutiny is how well suppliers are protected against cyberattacks – an issue of increasing magnitude, as cybercriminals are now adept at sniffing out vulnerabilities among suppliers that could allow them to infiltrate further and penetrate the systems of their ultimate targets.

Security experts often cite the SolarWinds hack of 2020 as a textbook example of a supply chain attack. Cybercriminals infiltrated the IT management software of the American software company and were then able to spread malware via regular software updates, compromising thousands of corporate networks around the world. So it is hardly surprising that half of the companies polled in the ‘Supply Chain Plans 2024’ survey by Software Advice signaled plans to up their investment in cybersecurity. In 2023, a full 43 percent of the surveyed companies had experienced operational disruption as a direct result of cyberattacks.

End-to-end supply chain visibility is also fundamental to achieving the much aspired-to circular economy, in which end-of-life products become raw materials for new products. To quote Dr Hanno Brümmer, executive vice president of supply chain and logistics at Covestro, speaking after a recent meeting of supply chain experts from the chemicals industry: “The contribution of the supply chain for sustainability will be crucial – both in terms of direct Scope 3 emissions and in enabling the transformation of the chemical industry to circularity.” Speaking in a similar vein, Dr Thomas Schamberg, senior vice president of supply chain at Evonik, commented at the ChemSCM 4.0 Summit in Berlin: “In most of my conversations, it was clear that we must reuse our resources. And to make that happen, we must connect our supply chains even more.”

2/3

of supply chain managers intend to invest in sustainability measures, according to a 2024 survey undertaken by Software Advice.

“A company that fails to stay on top of its supply chain will lose market share.”

Oliver Blum,

corporate director of supply chain, Endress+Hauser

DIGITALIZATION IS THE KEY

Supply chain managers seeking end-to-end visibility will be pleased to know that the digitalization experts have their back. “With Industry 4.0, we see increasing interconnection of systems to achieve end-to-end supply chain automation,” says Dr Felix Hanisch, president of the process automation users’ association NAMUR. “For this we need solid metrics – both from production plants and the market.” The point is that measurement data from warehouses and production facilities can be combined with logistics information to model supply chain and market behavior.

“We must reuse our resources. And to make that happen, we must connect our supply chains even more.”

Dr Thomas Schamberg

senior vice president of supply chain, Evonik

Digitalization and artificial intelligence play a key role in this process. They will increasingly enable agile responses by business owners to disruptions in the supply chain and help them realize digital business models. “We must continually rebalance the trade-offs between efficiency and resilience,” explains Oliver Blum, corporate director of supply chain at Endress+Hauser, “because a company that fails to stay on top of its supply chain will lose market share.” But from his perspective it’s about more than risk management, and the measures and methods deployed: “The most important thing is to have collaborative partnerships with external suppliers and service providers.”

Meanwhile, many brewers seem to have found a straightforward solution to the supply chain problem mentioned at the beginning of this piece. Instead of buying-in the carbon dioxide needed for their bottling processes, many now capture and reuse the carbon dioxide emitted during fermentation – a prime example of what is possible when process engineering and circularity work hand in hand.

About the author: Armin Scheuermann is a chemical engineer and journalist

+ 4.31

points was an all-time high reached in 2021 by the Global Supply Chain Pressure Index, a measure of the intensity of disruptions to global supply chains, at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. The historical average value is 0.

Published 04.11.2024, last updated 12.11.2024.

Dive into the world of the process industry through new exciting stories every month with our «changes» newsletter!